Book review: Everything Is Predictable

Tom Chivers has written a new popular science book on Bayes. I liked it and I have some thoughts.

You've probably come across math problems that sound something like this:

Werewolves have been terrorising the small town in which you are mayor and the people call on you to do something about it before the next full moon. Fortunately your trusted friend Dr. Von Silbermann has invented a useful blood test. If someone has werewolfism the test will give a positive result 98% of the time. If someone doesn't it will only give a positive result 2% of the time. You have no idea who might be a werewolf so you chose to start testing random citizens. Testing your nephew Clive you find, to your horror, a positive test result! What is the probability Clive is a werewolf?

It's easy to imagine the probability is 98%. The test says so right? But if you think about it for a minute, you haven't been told how common werewolfism is supposed to be. How big is the town? How many werewolves are there? Let's say there's a 1001 people in the town, and one werewolf terrorising it. If you tested everyone, sure, the test would most likely give a positive result for the werewolf, but it's also expected to give you a positive result for 20 innocent people (0.02 times 1000). That's a lot of innocent men and women hanging just to catch one werewolf. Talking about Clive specifically, the risk he's the werewolf is a bit less than 5%.

This formula is Bayes' rule. Tom Chivers’ latest book argues this math is everywhere. Not just in math problems about diagnosing stuff, or in real life problems involving diagnosing stuff, but in everything that has to do with uncertainty, prediction and rational decision making. Bayes explains almost everything. Even the brain. Even life!

Personally I'm not that sure it does explain everything, but I'm probably not fit to judge that either. Sometimes I'm unsure if I'm not quite following when "X is just a special case of Bayes", or if the metaphor actually is a bit loose. ("Everything" "here is hyperbole, Chivers doesn't think Bayes is all there is to all things either).

Before getting into specific topics I should be clear that I liked the book! Chivers sprinkels a dry British humor on his texts that makes for a fun read without distracting from the subject matter (if anything his style makes you feel smart and in on the joke). His explanations are easy to follow (except for the time there was a misprint on a completely essential graph!) and while the book is more broad than deep when it comes to Bayesianism, that fitted my brain perfectly well this summer (baby cute but bad for focus). If you're already familiar with Bayesianism you may still enjoy the historical parts about Thomas Bayes and later the statistics wars, but in the last part of the book (about the brain) you definitely feel that there's a lot of details being glossed over.

Statistics wars

Like most people in psychology and medical science, I've been trained in frequentist statistics and so the part of the book that was most personally relevant was about frequentist vs Bayesian statistics in science. (I admit frequentism didn't fully click for me until I took Daniël Lakens course, improving your statistical inference, which Chivers also repeatedly recommends in the book).

Chivers gives a fascinating but quick summary that goes from the birth of probability theory, the time where the solution to the werewolf problem was truly not yet known, to how Frequentists came to "win" the statistics wars (win in the sense that frequentism is the dominant mode of operating in science). The argument hinges on the idea that the statistical and scientific community were being uncomfortable with the idea of subjectivity in statistics; The biggest difference between Bayesian statistics is the inclusion of prior probabilities that are necessarily subjective.1 Frequentist interpretations of probability are based around the idea that probabilities are fundamentally about long-run frequencies. I.e. If you test a very large number of werewolves, 98% of your tests will give a positive result, and 2% will give a negative result because of randomness. This is how most people are used to think about probability. Even with this philosophy of probability you would use Bayes Theorem sometimes, but what Bayesians do is use these mathematical tools to describe degrees of conviction that something is true.

Let's instead take the question "what is the probability that the moon is made of cheese?" A frequentist might say that's a nonsense question. Probabilities pertain to long run frequencies! Either the moon is cheese or it isn't! But I think most people intuitively understand that probability can be used in the sense of "how confident are you?", just expressed numerically. Even though that can come off as a more informal way to talk about it, the Bayesian school of thought maintain that the more stringent math of probability can be effectively applied to confidence in subjective beliefs without any contradictions. You can split hairs about the philosophical meaning of the word probability, it doesn't really matter. The math works!

But since the this version of probability is about belief it inevitably needs a dose of subjectivity. When we're not dealing with a math text-book we're often dealing with some significant uncertainty about the state of the world. While the strength of evidence can sometimes be mathematically quantified, the prior probability that a given conclusion is true turns out to be personal and arbitrary. To go back to the werewolf example, we'd often find ourselves in situations where we trust Dr. Von Silbermann on the accuracy of the test, e.g. P(positive|werewolf). But on the other hand, we wouldn't really know how many werewolves are behind the series of attacks, e.g. P(werewolf). There we'd have to first do more informal guesswork based on the circumstances. Is it one werewolf behind multiple attacks or several? How many?

In Chivers' description it was this idea, that prior probabilities had to represent the ultimately subjective views of individual scientists, that historically gave Bayes an air of relativism that doomed it to (temporary) obscurity. He also brings up the idea (citing the book Bernoulli's Fallacy) that a desire for objective scientific authority for the eugenic views of many early frequentists like Fisher and Pearson2, but ultimately disagrees (which I think reflects well on the book). Regardless off what weighs heavier, frequentism becoming dominant wasn’t historically inevitable, but rather a pretty arbitrary outcome.

Subjectivity is unavoidable, since science is carried out by human individual scientists (subjects). In statistics and science you're constantly making modelling decisions that affect your outcome, regardless if you're doing frequentist or Bayesian statistics. Furthermore, when you get your numerical results, those are inevitably interpreted by your squishy human brain. I don't think many modern users of classical frequentist statistics would maintain that there's no subjectivity in science. Still the subjectivity in Bayesianism seems more built in.

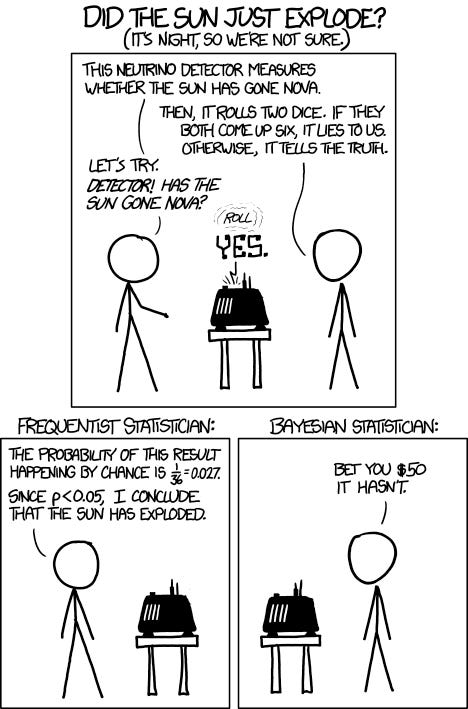

When reading about these statistics wars, one thing that strikes me is that there's something unavoidable about the Bayesian framework: The prior probability of a hypothesis being correct unavoidably affects how you should interpret your current state of knowledge after the evidence has come in. If you're going to do use statistical modelling in betting you're basically forced to do Bayes. But even so, there's still room for disagreement about what a scientific paper should do. Should the statistical content of the scientific paper contain the authors subjective priors? In Bayesian statistics the interpretation is integrated into the numbers (via priors), while frequentism is based around separating signal from noise, and then do an interpretation by just reasoning about it non-mathematically. Bayesians may often point out that frequentists treat P(Data|Hypothesis) as if it was P(Hypothesis|Data)3. See for example this xkcd comic:

But this joke in the comic above is often treated as a serious argument, and I think it's a straw man. Frequentists don't stop thinking the moment they see a significant p-value. Hopefully if they see something unbelievable they don't believe it. Right?

Right?

Is frequentism the cause of the replication crisis?

Chivers frames his discussion about Bayes in science around one famous social psychologist that did not think reasonably about what's likely after obtaining a significant p-value, but instead chose the path of endorsing parapsychology. I won't summarize the story in detail (I think most readers know it) but the short of it is that Daryl Bem, previously a well respected social psychologist seemed to do science properly and without cheating but was still able to get and publish results where participants showed supernatural precognition. Since he seemed to have done his homework (and had some prior credibility) he managed to get published in an prestigious psychology journal. This impossible mix of supernatural claims in ordinary ivory tower academia was one of the essential sparks that kicked off the cultural moment people call "the replication crisis in psychology", where researchers started to think long and hard about what they're actually doing. I think it's fair to say that a lot of psychological science was (and still is) ritual. Things are done simply because they're tradition or habit, rather than being done for logically sensible reasons by people who understand why they're doing it. Importantly large scale replication studies that sampled the literature revealed that only a minority of studies replicated!

Chivers (via Eric-Jan Wagenmakers) presents the case that frequentist statistics were essential for this fucked up state of affairs. He brings up some truly perverse examples of scientists proudly p-hacking without even seeing the problem, something that was basically standard practice at the time, sometimes even explicitly recommended. Poor understandings of p-values are easy to come by. But crucially Chivers mean that the problem lies in the p-values themselves. Since p-values are supposed to be uniformly distributed if the null hypothesis is true, they're inevitably kind of volatile. Running a small experiment based on some very unlikely hypothesis that is actually false (let's say something like unconscious social priming affecting walking speed) will be just as likely to turn up a significant p-value as a large study based on some pretty plausible hypothesis, given that hypothesis is actually false. So in a culture where publishing papers is necessary for advancing your academic career and significant p-values are key to getting published, a cynical scientist would be incentivized to run several low quality studies above few high-quality ones. Relying on Bayes Factors supposedly protects against this since a low n study can never be strong evidence. And even if you're a honest scientist, relying on p-values as your only signal would lead you chasing red herrings all the time. At least that's the case Chives presents.

But to get back to the question whether frequentists stop thinking the moment they see a significant p-value, the answer is in my opinion obviously no. When a surprising p-value turns up my colleagues attend to all sorts of potential sources of error. Evaluating a study is a complex and contextual skill-set. Perhaps it's better to include these sources of errors in the statistics, perhaps not. But you wouldn’t get away from these non mathematical sources of error/quality by using Bayes instead, and it's clear to me that the conditions that created the replication crisis are more complicated than just an overreliance on p-values (I think Chivers would agree there). The problem with running around chasing bad leads also lessens a lot if we imagine scientists that aren’t looking at various variants of parapsychology, but instead at things that could very well be true.

One thing that strikes me when I see people debate this is that both sides tend to imagine an ideal implementation of their statistical philosophy. But since most science is not that great, maybe the more important issue is what is worse: bad frequentism or bad bayesianism? Personally, I'm pretty convinced that given the incentive structures that exist within academia, people would find ways to misuse Bayesianism in very similar ways to frequentism. This seems doubly true for Bayesian proposals about dichotomous decision rules that look suspiciously similar to p-values at the end of the day4. According to "the natural selection of bad science", incentives to publish positive results together with the fact that being careful takes resources are likely to be enough to create bad science. Negative, unsexy results could be equally hard to publish in a world dominated by Bayesianism. In our current timeline we've seen a lot of textbooks deal with p-values in a way that has led to a lot of misleading bullshit, but in an alternate universe where Bayes had won the statistics wars I think similarly bastardized rituals around Bayes would have emerged through the process of natural selection. Whatever statistical approach we chose, we also have to do it well.

A case study on Bayesian reasoning

Flawless, or even good, implementation of anything is extremely difficult and perhaps not the right goal. The Rootclaim debate on Covid Origins is perhaps an interesting case-study here, despite it being outside academia and science. Rootclaim tries to apply mathematically rigorous Bayesian reasoning on fuzzy real world problems, like "did Assad use chemical weapons in Syria?" or "did covid originate in a lab?"

Not just Bayesian inspired thinking or thinking probabilistically, but actually trying to map out and correctly weigh together all relevant evidence according to Bayes, numbers and all. The details around the Rootclaim debate are a bit complicated but my overall impression is that this seemingly mathematically rigorous method unfortunately didn't work out all that well. If anything, the method seemed vulnerable to compounding and amplifying bias, rather than counteracting it. The judges and the opponent in the debate all simultaneously applied the method and ended up with wildly different estimates and in the end the judges didn't appear to take the precise mathematical estimates that seriously anyway. The winner of the debate (Peter Miller) was not basing his approach on any formal math but instead just thought carefully and logically about the problem. That doesn't mean he wasn't reasoning probabilistically on some level, but rather he seemed to trust that weighing which arguments make more sense and are more relevant is something humans are able to do without a spreadsheet.

To get back to the statistics wars in science, my impression is that one could easily argue that actual scientific conclusions are better left as this type of informal, non-mathematical, reasoning. When trying to map out all probabilities and evidence strengths exactly, you'll end up in a chaotic tangle. As long as what you're investigating is somewhat complex, it's just too much to consider and doing this poorly could instead lead you more astray. At least that's my impression.

A counterargument would be that humans are usually very bad at statistical thinking. Without hard math to fall back on, we instead rely on System 1, forming vibes-based impressions while believeing we're doing strict logic. Pushing Bayesian math onto your epistemology at least forces you to think more carefully about the problem. One could also claim that the reasoning a right thinking frequentist does is "implicitly Bayesian", but I wouldn't count that as a win in the statistics wars. Everything seems to be implicitly Bayesian, indeed that's the overarching point of the book. What I wonder is how implicit that implicitness is?

Bayes everywhere?

Not all who call themselves Bayesians are people who actually use statistics software to do statistical modelling. Some people who call themselves Bayesians are instead influenced by writings such as Elezier Yudkowsky's website less wrong (which Chivers cite in the book). I bring this up because I think there's a risk of muddying the waters a bit. It seems entirely consistent to think that Bayesian methods are preferable in science, while also not believing Bayesianism is the be all end all of epistemology more generally. And vice versa, one could be greatly sympathetic to the idea that Bayes’ rule is everywhere in the world, while still believing that frequentism is fine in some contexts.

This everything aspect, framing Bayes rule as the same thing regardless of where it turns up, is something I felt a bit sceptical about beforehand. Math is always abstraction, but I sometimes struggle with understanding how loose the metaphor is. How Bayesian are the self identified Bayesians really?

For example, Chivers talk about Philip Tetlock's work on forecasting. Tetlock is probably most famous for showing that experts (on average) are almost as bad as random chance when trying to make specific time limited predictions.5 But that's the average expert. His more important work, in my opinion, has been to study what distinguishes the best forecasters (what he calls Superforecasters). One of the things he found was that forecasters are good at thinking about conditional probability. For example if you are asked to predict the probability that Joe Biden will win the 2024 election, most would look at the polls and take it from there but would forget to account for the chance that Biden drops out of the race due to age related health issues resulting in a catastrophic debate performance.

Still, one of the the superforecasters Chivers interviews says he's not "explicitly plugging things in to Bayes' law, but it was certainly conceptually the model that I implicitly used." A solid understanding of probability, or a strong habit of thinking probabilistically, seems to be a necessary ingredient for a good forecaster. Good forecasters break things down into pieces.

Still, I wonder if some significant portion of this may fall under just reasoning carefully in some more informal sense. Thinking up additional things that can happen, additional necessary conditions, additional sources of uncertainty. In Scott Alexanders review of the Rootclaim debate mentioned earlier he calls what they're doing "Full Luxury Bayes", as opposed to “normal Bayesian reasoning”.

But the joke goes that you do Bayesian reasoning by doing normal reasoning while muttering “Bayes, Bayes, Bayes” under your breath. Nobody - not the statisticians, not Nate Silver, certainly not me - tries to do full Bayesian reasoning on fuzzy real-world problems

Nate Silver, another public face of Bayesian reasoning, in his book The Signal and The Noise cautioned against blindly trusting your model and instead advocated for some mix of expert human judgement with an understanding of probability and statistical models. You need to understand the model well enough to understand when it's acting weird, and understand what type of information the model isn't able to take in. But Silver's area is stuff like election forecasting by aggregating polls. In a lot of other cases we're instead dealing with epistemic issues that seems to be of a different kind. The degree to which explicit use of mathematical tools help there is still unclear to me.

At the same time, stepping too far away from the math and talking about being "implicitly Bayesian" is also a bit meaningless as an ideal. Some people identifying as Bayesian seem to simply mean they're people who adjust their belief in proportion to the strength of evidence - which is something I believe most people believe about themselves anyway. Using the phrase "I'm updating my priors" doesn't really do anything extra.

The final chapter of the book, save the epilogue, is about the brain. I've previously been sceptical about whether "the Brain is Bayesian" is actually a good description of perception, or if it's more like a useful analogy people use to explain perception to people who are used to thinking about Bayesian inference. On one hand perception is unavoidably a reverse inference problem, the brain is forced to find the best explanation given the data. So one could say: "If you're solving a reverse inference problem, you have to do something Bayesian, thus the brain is Bayesian." Maybe I'm bad at abstracting, or I maybe have some contrarian tendency that resists deep insight, but I find that a bit unsatisfying. When Chivers later tell us about Karl Friston's idea that evolution itself is also Bayesian (genes as priors predicting what challenges the organism will face) I do wonder whether we've gotten a bit too far away from the werewolf problem.

Because of this reluctance to connect everything I was fascinated to read about an experiment on multi-modal perception where the uncertainty in the signal from one sense was systematically varied. The result was that the integration from touch and sight weighed by uncertainty followed almost ideal Bayesian maths! I've not looked into this in any detail but my impression has been both that Bayes has been a useful framework for neuroscience, and sometimes been a buzzword that doesn't add that much. At worst people end up redescribing things we already believe with different words, at best it's a path towards an actually deeper understanding of the brain and the mind. That's a bet with positive utility if I ever saw one. Buzzwords aren’t that bad.

Conclusion

I postponed finishing this review several months because writing parts of it made me feel like I was about to embarrass myself. Problems in probability theory often have a deceptive quality, and I started worrying that I had missed some obvious things. But even though there's no shortage of strong opinions around this stuff, intelligent people seem to disagree. I think regardless of what mistake I've made I'm probably in good company.

When it comes to Bayes rule being a deep important insight that's pretty much everywhere, Chivers won me over in the end. But I'm still unconvinced that Bayes should have won the statistics wars or that it's the best way forward right now. Correctly interpreted and carefully applied Frequentism seems perfectly fine to me. The critics would say that the misinterpretations re-emerge naturally, but I'm not insightful enough about the Bayesian solutions to evaluate what misinterpretations may emerge there instead. However I do think that, speaking purely practically, most scientists are already frequentists. That means the distance from bad frequentism to good frequentism is probably shorter than the distance to good Bayesianism. If I were to view using Bayesian models in science as synonymous with using the absolute correct scientific epistemology the longer journey would be worth it, but I don't think that is the case. I think it's one tool among many.

Though there are people that disagree about this and say you can do Bayesianism without any pesky “subjectivity”.

But not Neyman, he was a bro.

So to be a bit more detailed: frequentist p-values aren't exactly P(Data|Hypothesis) either. They're P(getting data as or more extreme than D|null hypothesis) and are meant to be used as a dichotomous criteria.

Not denying that there are also important differences.

I guess this must depend on the difficulty of the questions (?) it was some years since I read Superforecasting..